The Best Books for Caregivers (not your normal list)

When I began caregiving, I went on Amazon and found books for caregivers. I read caregiver blogs, magazine articles, searched websites, and when I hired an aide, I spoke to the owner of that company at length.

I found a great deal about Alzheimer's, caregiver resources, financial and legal advice, caregivers' meditations, tips, blogs, suggestions, and caregiver stories. I was encouraged to take care of myself, seek support, attend monthly meetings and remember that "this too shall pass."

I was encouraged by all the resources, yet I didn't find anything that resonated with me. I didn't find an approach to caregiving that I could adopt or a new perspective to address my suffering. I was losing my relationship with my wife. She became a patient to me. Something was amiss, but I didn't know what it was. No one around me knew either.

Then I found a teacher/mentor/counselor to help who steered me in the direction I sought. Yet, I still wanted something to read that supported the new direction. I wanted to see it in print. Study it. Re-read it and have it be a comfort to me.

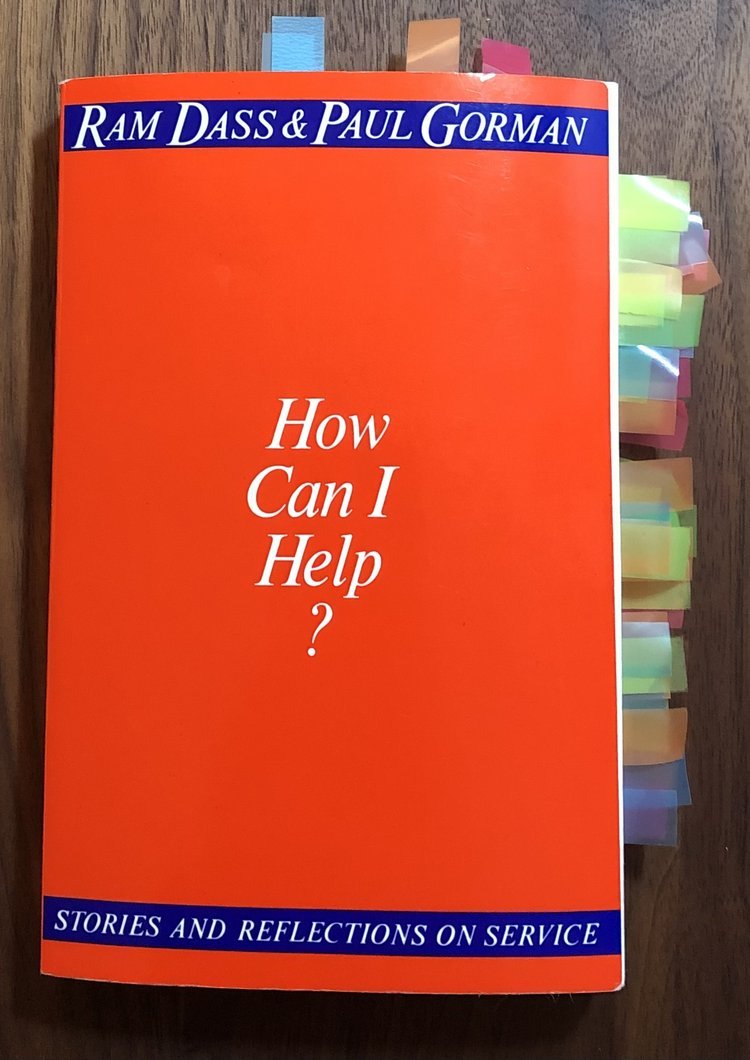

I found two books. How Can I Help? by Ram Dass & Paul Gorman. And The Yoga of Objectivity by Swami Dayananda Saraswati (and every other book or pamphlet he wrote).

Not your typical books for a caregiver but a great comfort to me. As you can see from the photos, I highlighted many passages that I've re-read numerous times.

Both books focus on the inner journey of the caregiver, a new view of reality, a path to find freedom from the suffering and dis-ease of caregiving.

This statement from How Can I Help? sums up the work in front of us.

We work on ourselves in order to help others. And we help others as a vehicle for working on ourselves.

The work is to take advantage of the transformational opportunity that caregiving affords. A dive into understanding your Self. A desire to remove any and all obstacles to a more intimate relationship with the person in your care.

"In the early stages of my father's cancer, I found it very difficult to know how best to help. I lived a thousand miles away and would come for visits. It was hard seeing him going downhill, harder still feeling so clumsy, not sure what to do, not sure what to say.

Toward the end, I was called to come suddenly. He'd been slipping. I went straight from the airport to the hospital, then directly to the room he was listed in.

When I entered, I saw that I had made a mistake. There was a very, very old man there, pale and hairless, thin, and breathing with great gasps, fast asleep, seemingly near death. So I turned to find my dad's room. Then I froze. I suddenly realized, "My God, that's him!" I hadn't recognized my own father. It was the single most shocking moment of my life.

Thank God he was asleep. All I could do was sit next to him and try to get past this image before he woke up and saw my shock. I had to look through him and find something beside this astonishing appearance of a father I could barely recognize physically.

By the time he awoke, I'd gotten part of the way. But we were still quite uncomfortable with one another. There was still this sense of distance. We both could feel it. It was very painful. We were both self-conscious…infrequent eye contact.

Several days later, I came into his room and found him asleep again. Again, such a hard sight. So I sat and looked some more.

Suddenly, this thought came to me, words of Mother Teresa, describing lepers she cared for as "Christ in all his distressing disguises."

I never had any real relation to Christ at all, and I can't say that I did at that moment. But what came through to me was a feeling for my father's identity…as like a child of God. That was who he really was behind the "distressing disguise." And it was my real identity to, I felt. I felt a great bond with him, which wasn't anything like I'd felt as father and daughter.

At that point, he woke up and looked at me and said, "Hi". And I looked at him and said, "Hi."

For the remaining months of his life, we were totally at peace and comfortable together. No more self-consciousness. No unfinished business. I usually seemed to know just what was needed. I could feed him, shave him, bathe him, hold him up to fix the pillows-all these very intimate things that had been so hard for me earlier.

In a way, this was my father's final gift to me: the chance to see him as something more than my father, the chance to see the common identity of spirit we both shared; the chance to see just how much that makes possible, in the way of love and comfort. And I feel I can call on it now with anyone else. How Can I Help?

When I finally committed to caregiving, when I stopped treating it as an interruption in my life; when I dropped my fears and doubts about what I was to do and who was in my care; I discovered love for my wife again. No longer did I se her or treat her as a patient.

I could love her as a whole and complete person. Worry and doubt and fear dropped away. I freed her from my attitudes and released her to be herself.

I've been chronically ill for twelve years. Stroke. Paralysis. That's what I'm dealing with now. I've gone to rehab program after rehab program. I may be one of the most rehabilitated people on the face of the earth. I should be President.

I've worked with a lot of people, and I've seen many types and attitudes. People try very hard to help me do my best on my own. They understand the importance of that self-sufficiency, and so do I. They're positive and optimistic. I admire them for their perseverance. My body is broken, but they still work very hard with it. They're very dedicated. I have nothing but respect for them.

But I must say this: I have never, ever, met someone who sees me as whole…

Can you understand this? Can you? No one sees me and helps me se myself as being complete, as is. No one really sees how that's true, at the deepest level. Everything else is Band-Aids, you know.

Now I understand that this is what I've got to see for myself, my own wholeness. But when you're talking about what really hurts, and about what I'm really not getting from those who're trying to help me… that's it: that feeling of not being seen as whole. How Can I Help?

The second book and in fact all the books/pamphlets by Swami Dayananda Saraswati represent a brilliant exposition on the nature of reality, of a way to know your Self.

The ability to see objectively as a caregiver is critical. Instead of seeing what we want to see, instead of imagining what we want to happen, instead of living in a ‘should’ mindset we see clearly and act dispassionately.

When I placed my wife into a memory care facility and the nurse asked me If I wanted to talk about the benefits of hospice care I said yes. Saying yes wasn’t jinxing her life in any way. In fact, she received additional care because I said yes. Many people fear to deal with hospice because it appears they are giving up the fight prematurely. Nothing could be further from the truth. My wife would die from Alzheimer’s sooner or later. Wishing and hoping wouldn’t change that fact.

So, the challenge we face as caregivers is to see the facts in front of us which is what Swami Dayananda Saraswati presents in his book, The Yoga of Objectivity.

We have in the Bhagavad Gita and its source book, the Upanishad, wisdom that we can call the Yoga of objectivity. To be objective is to face what is. It means not projecting ourselves into situations. People hardly take things as they are but look at things in terms of how they should be – how their people should be; how other people should be even if they are not known to them.

To be objective, we need to know that what is here is 'given.' To be objective, eyes and ears are not enough. We need to know that each one of us is living in a world that is not just out there always, but in a world that is often here in our head.

To be objective is to understand that there are many hidden variables beyond our control. Our perception of the world is conditioned by what it should have been, what it should be and should not be. It is how we look at the world. It is in our head.

This 'should be' is inevitable. I find that a situation has to be reorganized or has to be changed so that I feel comfortable. It is what planning is, what execution is. It is what intelligent living is. I need to bring about desirable changes. I cannot say this is how it is and therefore let it be. No. That I need to bring about changes is not negotiable, and that I am not able to bring about all those changes that I want is a reality. How I respond to the reality, more often than not, is subjective, the agonies, the regrets, the frustrations, the ulcers. They are my own creations because I can be different. I need not undergo these inner upheavals. I can face things squarely and continue to be objective without subjecting myself to ups and downs, to 'yoyo' emotions. When I am objective to the world, I know that some changes need to be brought about that will make a difference in the lives of people.

Therefore, I do what I need to do, recognizing that I am not in charge; I do not call all the shots. There are so many hidden variables, and I am not able to control all of them. I cannot control even a known variable, let alone hidden variables, and there are so many of them. It is imperative that I learn a few things in order to be objective to the varying situations in life, pleasant and unpleasant. The sameness of mind towards the pleasant and unpleasant is said to be yoga in the Gita. The Yoga of Objectivity

As I said at the beginning these are two uncommon books for the caregiver but both brought me great satisfaction. Add them to your bookshelves. Read them. They are by far the best books for a caregiver.

If you’re a caregiver having difficulty in this role, feeling alone, frustrated and tired with no peers to share your experiences, on a rollercoaster ride of doctor calls and appointments, bouncing between good news and bad news, having more questions than answers, suffering as you’ve seen others suffer, having tried what everyone has said to try but to no avail, then you may be ready for a fundamentally different approach.